Imran Khan has represented the Lawrence family for twenty years. He spoke to Oliver Lewis, who was his trainee when the initial Lawrence investigation was going on, and reflected on the case, his career and what has inspired him.

Part One: The East End, Racism and the Lawrence Case.

Imran Khan’s career has developed in a way he could scarcely have predicted when he qualified as a solicitor in 1991. Less than two years later he was approached and asked if he would represent the devastated Lawrence family whose son Stephen had been the victim of a brutal racist murder in Eltham. The men arrested had the charges dropped. After an unsuccessful private prosecution and years of campaigning, the McPherson inquiry concluded that there was institutional racism in the police force. In 2012 two men were finally convicted of the murder and jailed for life.

A busy man, Imran Khan is for once in his office, nestled between high Holborn and Bloomsbury. The lawyerly, almost genteel setting is a far cry from his early days growing up in east London where he suffered himself at the hands of racists. He traces his determination to make a difference in society to that experience.

“It was every day, going to school facing the trials and tribulations of avoiding a kicking because of the colour of your skin, and you thought, ‘Why isn’t any one doing anything about this?’ You realised there is a reality that most of society doesn’t believe or doesn’t want to believe exists. Living in the east end of London with racists and football hooligans, it was a very different place to what it is now, and there wasn’t any one around who said ‘I know that reality, I want to do something about it and change it’.”

A campaigning voice

Later, working with the anti-racist community group, Newham Monitoring Project, he was influenced by a group of lawyers who started doing things differently in the late 1970s and early 1980s. One of his most vivid memories was sitting in the public gallery in the Old Bailey during the Newham Seven trial. A group of Asian men faced trial for affray after the East End Asian community had been subject to violent racist attacks.

“Their defence was self-defence, and back then it was so hard to bring the issue of racism into court, so it was absolutely pivotal seeing that inflexibility of the court being challenged by the likes of Mike Mansfield and Rudy Nurayan. They were saying ‘You can’t look at the law in isolation, you’ve got to look at it in the context of wider society.’ I had suffered that racism and I suddenly realised that these wigged, intelligent people were articulating my living reality, and in this grand building! It suddenly dawned on me here was a way of changing society for the better. That’s what got me involved, I suddenly realised that there was a campaigning voice.”

Question everything

Instead of a planned career in medicine he enrolled to do a law degree at North East London Polytechnic (now the University of East London) and at the same time began working at Birnbergs solicitors alongside Gareth Peirce. Those experiences in tandem were also formative.

“Almost on a daily basis I would be clerking cases where a young black man would be saying ‘I was fitted up by the police,’ or ‘This was planted on me.’ It was such a regular occurrence, it was frightening. All lawyers know how difficult it is to be in a court with a judge who is completely against your client, and we were fighting an uphill struggle in a way that few people would believe now. Judges wouldn’t allow any idea of racism into the courtroom, so it was brave for that much more vocal, radical group of lawyers to do it. It seemed underground and rebellious at the time and it was incredibly exciting.”

At the same time Imran Khan was absorbing the academic side of the law. He was influenced by lecturers whose message was question everything, don’t just accept things for what they are. Studying The Politics of Judiciary by JAG Griffiths was significant too.

“What I got from my lecturers was that it wasn’t just about law, it was about reading between the lines. They would not just talk about the decision but why the court came to that decision. You mustn’t just see the decisions at face value but put them in context.”

And he was seeing the reality of that in court. “These were lawyers who were prepared to argue and fight for their clients in a way that hadn’t happened before, so there was already a sense that this layer of lawyers was prepared to say ‘We will take that fight on!’ Maybe the timing was right for me, if people like Mike (Mansfield) and Helena (Kennedy) hadn’t been there I would have seen law as a clinical abstract thing that everyone said it was, so I have been fortunate to be in the right place at the right time. Seeing lawyers in everyday circumstances trying to do good by the community was completely inspirational.”

He says the justice system has come far since those days.

“It’s another world from when I started in law in lots of different ways. If I went into a courtroom when I became a lawyer in 1991 and one now, they would be two completely different environments. The judiciary is changing in terms of its approach, the bar has changed incredibly in terms of its diversity, and so has the way people view rights. We’re not there yet though. I was in a long trial in Birmingham recently and nearly all of the representatives were from ethnic minorities, although there was not a single one on the bench and you think, how does that happen?”

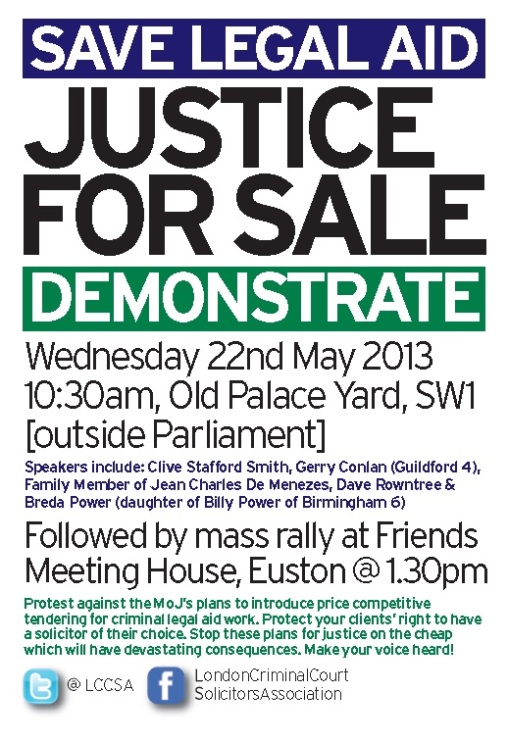

An erosion of rights

It’s now almost precisely twenty years since Stephen Lawrence was murdered, and the impact of the case across society has been great, but not always, he acknowledges, in ways that were always foreseeable or desirable. He regrets the way the case has occasionally been used to advance arguments with which he hasn’t agreed. He says the Lawrence case has on occasion been hijacked to promote the removal of rights.

“The thing I do regret about the Lawrence case is that it was supposed to be about extending rights to victims, but that banner was used not to promote victims’ rights but actually to erode rights. Governments and certain sections of the media have used the Lawrence case saying, ‘Because the Lawrence family didn’t get justice and suspects have hidden behind various things, we must change things. We need to stop people hiding behind the Human Rights Act etc.’ The right took it on because they saw it as a law and order issue.”

He says the case should have been about expanding rights for all, not denying them to people. “The case was about trying to get justice for a family, but you don’t get justice by removing rights. Because I am primarily and at heart a defence lawyer, that for me is not the way we should have gone, we shouldn’t have taken rights away from suspects. That is the only negative thing that has come out of the Lawrence case. Things are better in terms of the people around the system, but it’s worse in terms of the law in some ways. Now many rights have been taken away, the right to silence in the police station, for instance, and double jeopardy has come in.”

Imran Khan says the investigation of racist crimes has improved and, importantly, so has the ability to challenge racism. But, he says, racism still continues.

“It is as rife as it was, if not worse. You still have huge amounts of racism, but the way it comes out has changed. You used to have the National Front with their skinheads and bovver boots, you could see them and recognise them clear as the nose on your face, but now it’s the BNP wearing a suit and tie, still a racist but clothed in respectability. People find different ways of expressing racism, it hasn’t gone away, it’s just another way of expressing it. On the terraces it’s still there despite the Respect campaign. But what we have now that we didn’t have in 1991 is the mechanism to take action. That is the good thing to have come out of it. So in my cases now when I’m suing an authority or suing the police or taking action there is a legislative matrix that I can use to say, ‘This is what has gone wrong, I can give it a name,’ and people have to accept it.”

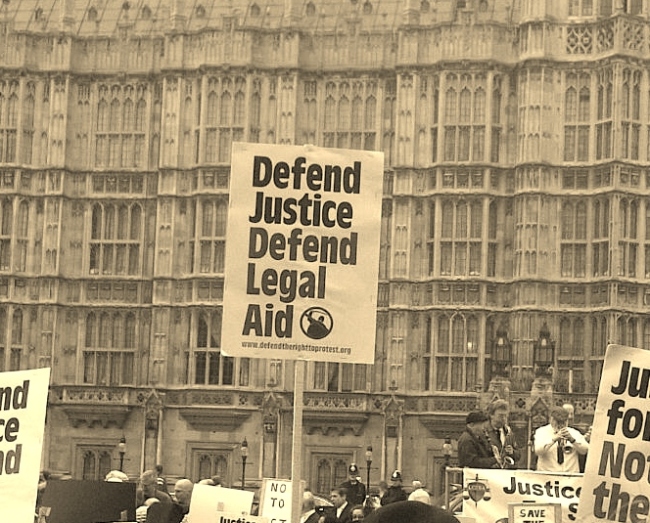

He says that makes a big difference. “In the old days it was nebulous, you could say someone was being treated in a racist fashion, and it would be ‘There’s no law stopping that, Mr. Khan.’ There was nothing you could do, and you had to fight politically, more in terms of community action, demonstrations in order to achieve some redress. Courts just wouldn’t allow it, so if you were arguing self-defence, racism wasn’t permitted to come into it, the contextualisation of it wasn’t permitted. So the good thing is it is now accepted, and it is acknowledged. Does it change the reality in which people live? Probably not. But for lawyers like me, what we didn’t have in 1991 was the ability to take that on.”

The biggest achievement

The McPherson report recommended changes to policing as well as measures to extend rights for victims of crime and redefine offences classified as racist. That, says Imran Khan, is the major impact the Lawrence case had on society.

“The case hasn’t just changed things for the black community, it has changed things for everybody. It’s not been about improving the lot of black people who come into contact with the police service, it’s about when everybody comes into contact with the police, and it’s been about creating a better police service, transparency, accountability. That has changed for everybody. I remember the Brixton riots and Scarman, there was lip service but broadly the view was that there were a few bad apples. So it is that racism is now acknowledged and accepted, and that there has been an institutional, structural change. And for me, who’s been fighting on that front for many years from a community and political perspective, that is the biggest achievement.”

“If I go back and relate it to me growing up in east London, little kids could come up to you and spit on you and you couldn’t do anything about it, where someone could call you a name and you couldn’t do anything because you knew the whole of the system was against you. Now the system recognises that it is racist. That is huge, that is turning the tables completely, and for me it’s about society fundamentally accepting racism exists, and that there is a reality that is accepted by everybody, and I think that is a profound change.”

The case has had an impact on Imran Khan personally as well as on society more widely. He says it has been his proudest achievement to be associated with the case.

“As a professional you want to be proud of what you do and you want to think you have done something good, although I never thought in those moments in east London that I would be involved with something which has had such an impact across the board. I am astonished the sort of people who come and shake my hand and say I’ve done a good job, when I just think I have just done my job. That’s not out of false modesty, but it’s all I’ve ever wanted to do. I had six rugby type players on a packed tube train turn to me and I thought I was going to get my head kicked in, and they recognised me and said what a great job I was doing. That’s the impact it has had, and that is a huge source of pride.”

Is he surprised the case resonates still?

“Yes I am surprised! I’ve been doing it for twenty years, the fact that it still resonates is fantastic. It’s become iconic, it manages to symbolise everything in one word, and when do you get the chance to be part of that, almost by accident? It’s just been phenomenal.”

Coming soon: Part Two Beyond Lawrence and The Importance of Human Rights

A shorter version of this article first appeared at The Justice Gap.